James Jordan Johnson in conversation with Róise Goan

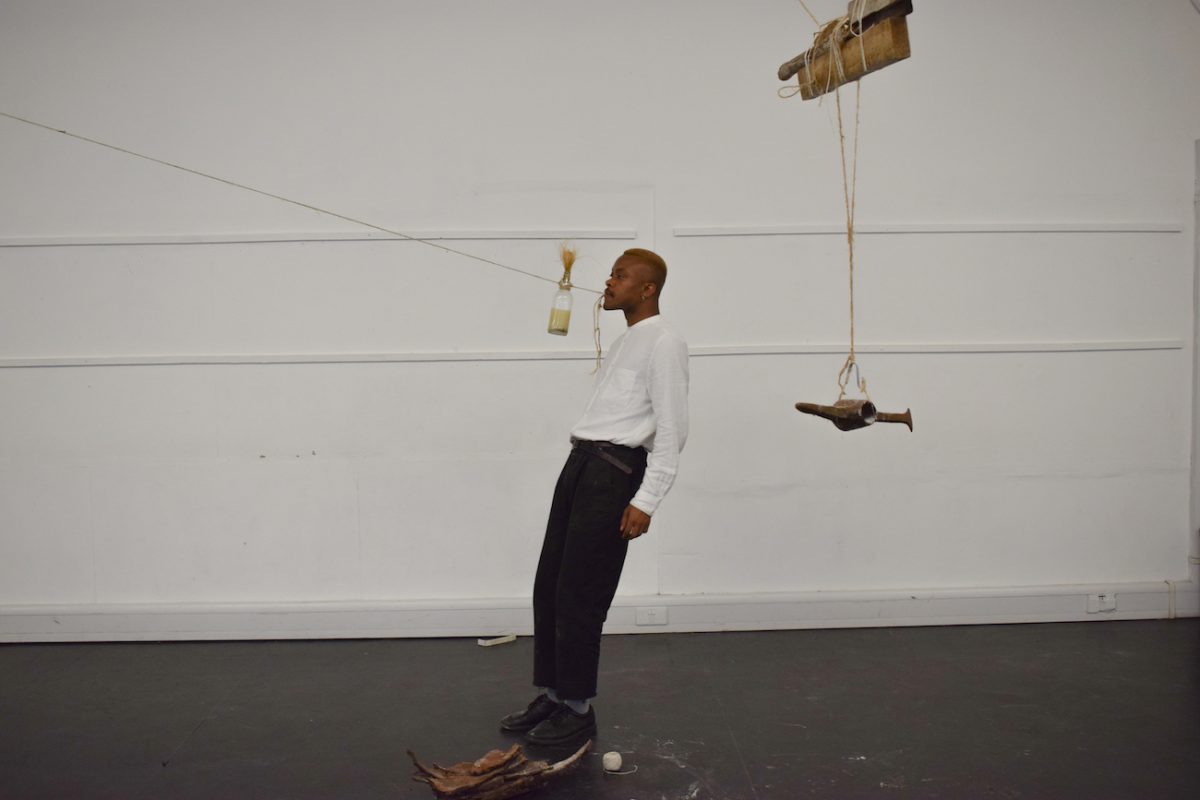

James Jordan Johnson is one of Artsadmin’s current Bursary recipients. As an artist belonging to the Caribbean diaspora, his practice explores the transnational, phantasmic, and everyday contours and possibilities of black performance traditions. Through performance, sculpture, and photography he explores the set of historical conditions that produce Afro-Caribbean memory.

In this interview with Róise Goan, Artsadmin’s Artistic Director, James shares his reflections on research and work developed at Artsadmin’s Toynbee Studios in summer 2020 for Working Encounters, which is part of an EU-funded collaborative project Create to Connect > Create to Impact.

Róise Goan: Tell us a little about the provocation PLANETARY SUPER-HEROISMS: On Villains, Aliens and Superheroes, and how that led you to present the first iteration on Negotiations of Obeah Material Memory: The Denigration of Material Belief Systems?

James Jordan Johnson: PLANETARY SUPER-HEROISMS: On Villains, Aliens and Superheroes was a project brief for Create to Connect -> Create to Impact. Create to Connect -> Create to Impact was a project bringing together fourteen cultural organisations and artists to create and establish a new means of cultural and artistic production. The project brief itself was really interesting to me because of how open-ended it was in its invitation for artists to respond to their relationship, concerns, interests and approaches to how heroes and villains are conceived.

What made me want to make this work was born out of a performance at Brixton Market with artist, collaborator and friend Jade Blackstock. I first came across Jade’s work on Instagram and felt this deep material and kinetic relationship to her work. There was this one performance where she’s performing on the street and spitting kidney beans out of her mouth. I remember seeing it for the first time and felt a familial connection to the work, I knew our performances both dealt with trying to demystify unexplainable experiences/articulations. What became clear to me through meeting Jade is how much I was grappling with these personal and historical gaps.

For me, performance itself was similar to when you realise your body is calling you to do something that you have to do but you’re not entirely sure about all of the reasons why or what ways to go about it. Well, everything made sense after meeting Jade.

After a few months of carefully watching Jade’s work, I later reached out to her asking that I wanted to do a performance with her on the streets of London, which then led to us deciding to do something at Brixton Market. For so many historical and personal reasons choosing Brixton felt right because, not only are we both of Jamaican heritage, our locality in Jamaica is intrinsically the same, being Clarendon. We initiated a date for the performance, however, we didn’t tell each other specifically what we would be doing from beginning to end, which left the work quite open. On the day of the performance I used a set of materials and actions that I had in mind for a while; to use sorrel, coconut husk (which I had been collecting for four months), a bucket, and water. The actions I performed included tying coconut husk to my feet, putting sorrel and water in my mouth and then spitting it back in the bucket over a period of time. Jade used a fish that was tied to a lamppost which she put in her mouth whilst holding a jar of milk in her hand. She began to lean back with the fish tied to the lamppost whilst the jar of milk started to spill down her leg.

In a few minutes, a huge crowd emerged around us, they were all intrigued by the work and it was a very intergenerational audience – the performance felt longer than it actually was because of the audience engagement. But what made this work special and how it informed my research for this project was the people’s responses to the performance. I spoke with Jade post-performance and she told me she heard someone saying that we were practicing Obeah. This is interesting as it’s known that Obeah is a cultural and spiritual practice that surrounds so much of our Caribbean history. When we think about what contributed to the emancipation and disruption of colonialism, it includes cultural and performative traditions. The performance and the reflections that followed it was on my mind a lot throughout this year. It was a catalyst for me which began my reading into Obeah more deeply. What I had read about Obeah was so different from what was culturally known/understood, I could not get that out of my mind. I wanted to use PLANETARY SUPER-HEROISMS: On Villains, Aliens, and Superheroes as an opportunity to respond to research, texts, and accounts through performance, objects, and materiality. To think about the history of non-western medicine as well as healing practices that were crucial to Caribbean and Black history at large.

R: This group of international artists, assembled for Working Encounters, was originally intended to meet/research/make in person, but due to COVID, the activity happened online. Was it possible to feel connected to a group of artists you don’t know in this context? What was that process like?

J: I thought about how the physical could have been a really interesting way to be in conversation with the other artists and to see how to mine and also their research could have made for an interesting collaboration, this is because I believe in knowledge/history exchanges. It was hard to feel connected because it all happened online, during COVID. The process involved setting up a group Google Drive where we could share texts and images. In one of our online meetings, Ivana Marjanović, one of the project Editors, shared a really useful project by The Otolith Group called Hydra Decapita, it allowed me to think about what is lost during destination points, which helped my research a lot. So the consultation sessions were really useful.

R: What next for your Negotiations of Obeah Material Memory Project?

J: For the second iteration, I want to work closely and extensively with other people such as historians specialising in Afro-Caribbean history and other Afro-Caribbean people such as my family, potentially including audio interviews. One thing about the next stage is that there is no urgency, so I would like to continue reading, most importantly, and to treat the work and history with the care it deserves.

Create to Connect -> Create to Impact is supported by the Creative Europe programme of the European Union. The residency at Toynbee Studios was supported through a grant from The Mayor of London’s Culture at Risk Business Support Fund and the Creative Land Trust.